- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

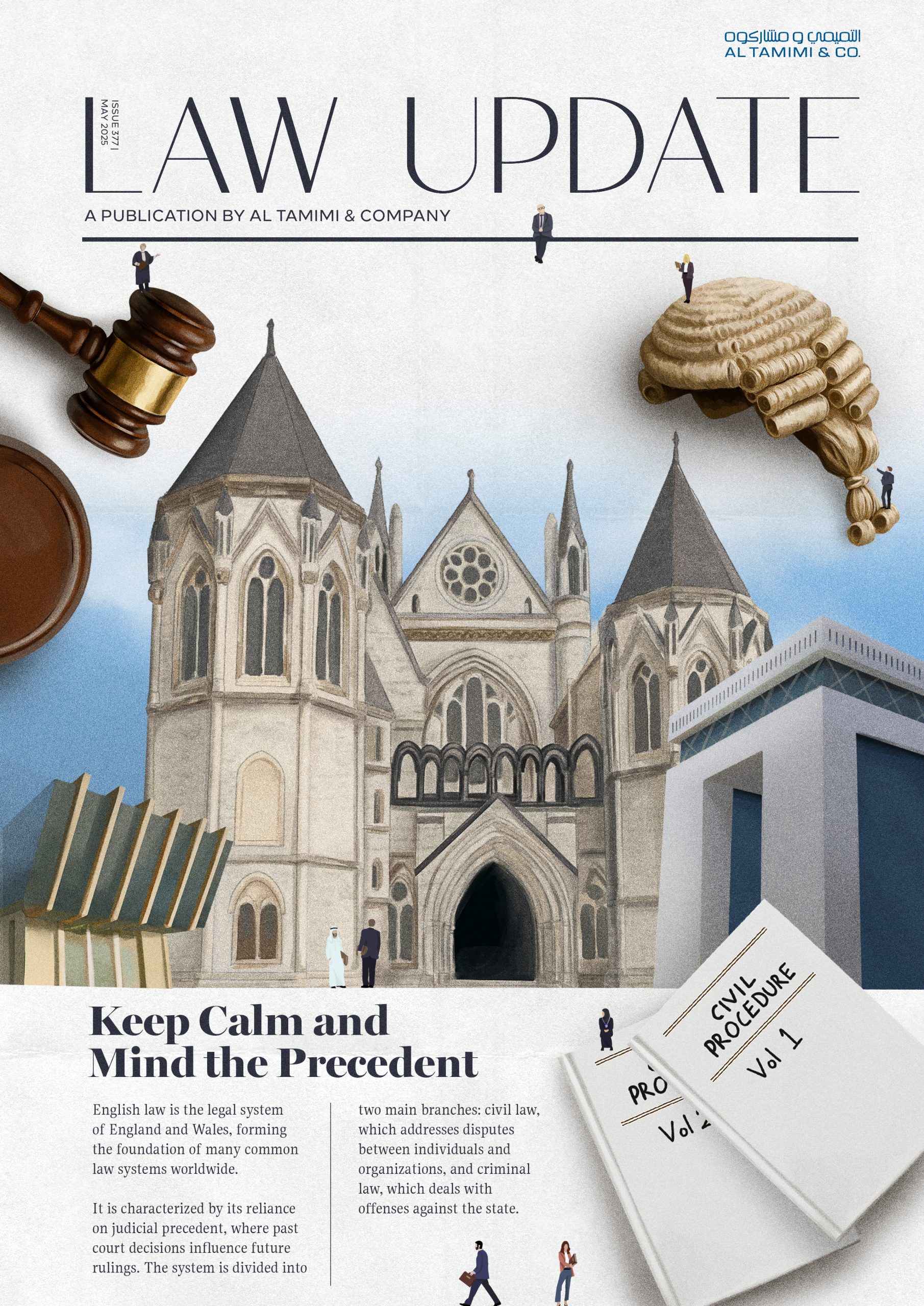

English Law: Keep calm and mind the precedent

In May Law Update’s edition, we examined the continued relevance of English law across MENA jurisdictions and why it remains a cornerstone of commercial transactions, dispute resolution, and cross-border deal structuring.

From the Dubai Court’s recognition of Without Prejudice communications to anti-sandbagging clauses, ESG, joint ventures, and the classification of warranties, our contributors explore how English legal concepts are being applied, interpreted, and adapted in a regional context.

With expert insight across sectors, including capital markets, corporate acquisitions, and estate planning, this issue underscores that familiarity with English law is no longer optional for businesses in MENA. It is essential.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- Technology, media, telecoms: past, present, and future

- /

- Cross-Border E-Commerce in the GCC – A Licensing Perspective

Cross-Border E-Commerce in the GCC – A Licensing Perspective

Nazanin Maghsoudlou - Senior Counsel - Corporate Structuring

Omer Khan - Partner - Corporate Structuring / Turnaround, Restructuring and Insolvency

What are the rules of engagement?

In the GCC, e-commerce – that part of the broader retail industry where a customer makes a purchase online – has three key characteristics.

First, it is lucrative. A report published by website design consultant GO-Gulf in late April 2021 noted that profits from e-commerce in the GCC countries amounted to US$20 billion in 2020.

Further, e-commerce is expanding rapidly. Across the broader Middle East & North Africa (“MENA”) region, sales in 2020 were an estimated US$55.4 billion; in 2015, the corresponding figure had been US$22.2 billion.

Finally, e-commerce across the MENA region involves goods that have been imported from elsewhere. Currently, two-thirds of online shoppers buy goods that are sourced from outside the region. Nearly 90% of the goods are imported; hence, there are substantial opportunities for cross-border e-commerce.

This is particularly true for consumer goods such as electronics, fashion & beauty, grocery, and home products – which make up 98% of e-commerce in the United Arab Emirates (“UAE”) and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (“KSA”). Along with Egypt, these countries account for about 80% of all e-commerce sales in the MENA region.

In comparison to the potential scalability of e-commerce across the GCC countries, the legal framework governing e-commerce is less clear and consistent especially when compared to other common markets, for example, across the European Union (EU) or the United States (US). In this article, we generally broach one aspect of this legal framework, that of corporate licencing requirements to undertake e-commerce in the GCC countries.

KSA – Arguably the regional leader

Relative to other GCC countries, KSA stands out because it has laws which specifically pertain to e-commerce. The KSA E-Commerce Law (Royal Decree No.M/126 of 2019) (“KSA E-Commerce Law”) and its associated regulations aim to regulate any and all transactions that involve local or foreign e-commerce providers and their customers within KSA.

Although, there are no specific licences or permits that are required for a foreign company to engage in e-commerce in the KSA, (i.e. no physical local presence would be required), but the e-commerce providers are still required to comply with the KSA E-Commerce Law provisions such as cancellations of orders, correction of errors, protection of customers’ personal data, e-store disclosures, invoicing and advertising.

Sanctions for violations of the KSA E-Commerce Law are varied. They include warnings, fines of up to SAR1,000,000, forced suspension of activity (either temporary or permanent) and – in extreme circumstances – electronic blocking of relevant online shops.

UAE – The more you do, the more the rules apply

In the UAE, Federal Law No. (1) of 2006 on Electronic Commerce and Transactions (“UAE E-Commerce Law”) is widely seen as the main piece of legislation governing e-commerce.

Article 3 of the UAE E-Commerce Law sets out its overall objectives and it seeks to protect the rights of people who are carrying out business electronically. However, its main focus is on electronic communications. For instance, the UAE E-Commerce Law seeks to minimise the incidence of forged electronic communications, to promote e-government (i.e. the online filing of necessary documents) and encourage the use of electronic signatures.

What the UAE E-Commerce Law does not do is discuss what are the licences that may be required of an e-commerce business that is seeking to reach customers in the UAE.

The provisions of Article 328 (1) of the Federal Law No. (2) of 2015 on Commercial Companies (“UAE Companies Law”) suggest that any foreign company wanting to do business within the UAE must obtain relevant licences to do so from the Federal Ministry of Economy and other competent authorities, and such licences usually require the establishment of a local entity.

What is less well defined is exactly what is meant by a company that is looking to do business in the UAE. A foreign e-commerce business that is accessible online to UAE residents will not automatically be seen as looking to transact within the country. However, if the e-commerce business actually employs people in the UAE or has advertising that is clearly targeting customers within the country, there is a significant likelihood that that foreign company will be seen as doing business in the UAE.

Sanctions for violations of the laws governing the UAE foreign investment and commercial registration can include fines of up to AED100,000.

Oman and Bahrain – Few apparent restrictions

In Oman, the relevant law governing e-commerce is the Electronic Transaction Law (2008).

Like its counterpart in the UAE, this Law focuses on electronic communications rather than on e-commerce itself.

Article 1 of the Foreign Capital Investment Law (1994) suggests that foreign entities are unable to conduct commercial business – or participate in an Omani company without a licence that has been issued by the Ministry of Commerce & Industry. This requirement generally applies regardless of the nature of the business being conducted in the country – and that includes e-commerce.

Sanctions for violation of the Electronic Transaction Law include up to one year’s imprisonment and/or a fine that is no greater than OMR1,500. This is of course without prejudice to any harsher punishment provided for by the Omani Penal Law, or any other laws.

In Bahrain, the 2018 Electronic Communications and Transactions Law (ECTL) and the Personal Data Protection Law allow for e-commerce: however, neither of these refer specifically to licences that should be held by e-commerce companies.

In line with Bahrain’s general laws, a person or entity that operates, or provides commercial services within Bahrain must have a legal presence there – underpinned by registration with the Bahrain Ministry of Industry Commerce & Tourism (“MOICT”). The application to MOICT would need to specify e-commerce activities.

Strictly speaking, according to Bahrain’s Commercial Registry Law No.27 of 2015, if a person or entity engages in e-commerce activities without having first obtained the relevant licence, then he/she may be punished by a prison term that does not exceed one year, and/or a fine between BHD1,000 and BHD100,000. However, in so far as a foreign entity is not facilitating/involved with the actual delivery of any real goods on the ground in Bahrain, and does not actually sell its own goods on the platform (i.e. the title to the said goods never passes to the entity, but rather, merely offers a means by which users can sell their goods on the platform), it is arguable that a local entity with the ‘retail sale by internet’ licence (i.e. e-commerce licence) may not be required.

Qatar

The legal framework governing e-commerce in Qatar has elements that are similar to that of KSA and the UAE.

As is the case in KSA, specific laws exist that recognise and govern e-commerce – and which seek to protect all stakeholders. A key piece of legislation is the Electronic Commerce and Transaction Law No.16 of 2010. Additionally, the Ministry of Transport and Communications has presented relevant provisions such as the Guidelines for E-Commerce Technology 2017/2018 and Guidelines for E-Commerce Security 2017/2018.

As is the case in the UAE, an e-commerce business that is seeking to do business in Qatar must generally be registered with the Ministry of Economy and Commerce, in accordance with the Commercial Register Law No. 2 of 2005. Operating a business in Qatar without the necessary licence(s) can incur a six-month period of imprisonment and/or a QAR50,000 fine. However, a foreign business that has no people in Qatar, no IP address in the country and that is not clearly seeking Qatari customers (even if it is easily accessible by them) will not necessarily be seen as doing business in the country: in this instance it will not be required to incorporate and register a local entity.

Conclusion

As a common approach, in each of the GCC countries the licencing regimes do require a company to apply for and have a licence to undertake commercial activities, meaning to have a registered office in form of a corporate presence. That being said, in case of e-commerce activates, there can be instances where this principle may not apply. However, such exclusion will depend on the nature and extent of the e-commerce operation, and hence, each case will need to be examined on a case by case basis to determine if an e-commerce operation can be conducted with or without a physical local presence / commercial licence.

Looking forward, the growth of e-commerce across the GCC region will probably result in greater focus on the regulatory frameworks governing online retailing in each of the different countries.

On balance, changes will likely make e-commerce easier – to support trends that are already in place.

In particular, it should become a lot clearer as to what are the activities that, if undertaken by a foreign e-commerce firm, will give rise for a licence to be needed for sales to customers in a particular jurisdiction.

As ever, the devil will be in the details…

This article is a general guide. It is not a substitute for professional advice which takes account of your specific circumstances and any changes in the law and practice. Subjects covered change constantly and develop. No responsibility can be accepted by Al Tamimi & Company or the authors for any loss occasioned by any person acting or refraining from acting on the basis of this.

Al Tamimi & Company’s Corporate Structuring teams across all our offices in the GCC regularly advise commercial entities on legal and regulatory developments impacting the e-commerce activities. For further information, please contact Omer Khan, Partner, or Nazanin Maghsoudlou, Senior Associate.

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.