- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Real Estate & Construction and Hotels & Leisure

Real estate, construction, and hospitality are at the forefront of transformation across the Middle East – reshaping cities, driving investment, and demanding increasingly sophisticated legal frameworks.

In the June edition of Law Update, we take a closer look at the legal shifts influencing the sector – from Dubai’s new Real Estate Investment Funds Law and major reforms in Qatar, to Bahrain’s push toward digitalisation in property and timeshare regulation. We also explore practical issues around strata, zoning, joint ventures, and hotel management agreements that are critical to navigating today’s market.

As the landscape becomes more complex, understanding the legal dynamics behind these developments is key to making informed, strategic decisions.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- Transport & Logistics

- /

- Tax Bullet Dodged for the Shipping Industry

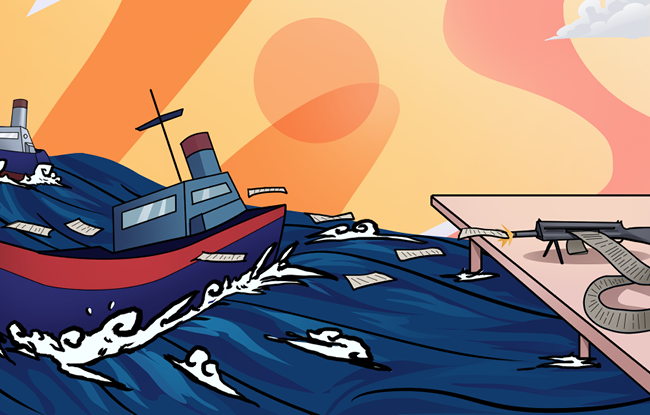

Tax Bullet Dodged for the Shipping Industry

Adam Gray - Senior Counsel (Consultant) - Shipping, Aviation & Logistics

On 1 July 2021, the OECD announced that an agreement had been reached between 130 countries, including the G20, on a new global minimum corporation tax regime. Prompted by “the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy”, in other words the desire to share in the eye-watering profits of ‘big-tech’ where those profits are earned, the new international deal will have a far-reaching impact on multi-nationals beyond the technology sector. It will apply to companies ranging from AstraZeneca to Unilever, Nissan to Anglo American. However, the Maersk’s of this world will not be touched, nor the shipping industry at large, which gained the only exemption granted, an announcement that was met with almost unanimous relief in the shipping sphere. Nonetheless, the OECD has said discussions will continue through to October and there is always potential for the broad exemption to be further defined and possibly narrowed.

What the International Tax Deal Involves

The move to introduce a global minimum corporation tax rate was motivated by the desire of nation States to share profits generated by multi-national companies but sheltered in low-tax jurisdictions. Additionally, achieving consensus on a tax floor would prevent a tax “race to the bottom” between competing States. An agreed floor protects their tax base and enables greater revenue certainty. This desire only intensified during the current pandemic era, when countries around the world issued unprecedented levels of debt to fund a global economic survival programme.

The current international taxation regime was not deemed “fit-for-purpose”, primarily because taxation rights attached only to nations in which the company has residence. This allowed high-revenue generating multi-nationals to register companies in ‘tax-havens’ to avoid larger tax liabilities, despite generating hundreds of millions or billions around the world. Many States installed low-tax regimes to attract business from multi-nationals and benefited from satellite economic growth associated with the presence of multi-nationals in their jurisdiction.

Under the deal, a parent company in a participating jurisdiction will be liable to pay a “top-up tax” up to 15% corporation tax if the subsidiary pays less corporation tax in a low-tax constituent jurisdiction. Accordingly, a subsidiary company paying 5% in a low tax jurisdiction will have the 10% difference topped up and paid by the parent company in the State of domicile. This will apply from 2023 to all companies earning more than EUR 750m per annum.

How might ship owners have been impacted?

Ship owners have employed this tax-minimisation strategy for the best part of a century and countries with popular open-registries have been rewarded handsomely, such as Liberia, Panama and the Marshall Islands. Many shipping companies pay no corporation tax at all in some jurisdictions, but the surrounding service sector flourishes, in turn bolstering State income and creating local jobs.

Additionally, corporation tax is often calculated through tonnage tax systems, whereby the actual income and expenditure is substituted by a relatively low, tonnage-linked, assumed daily profit. This tax is often in the single digit figures and offers certainty to shipowners in a volatile and cyclical industry.

It follows that the imposition of the global minimum corporation tax rate would have been ruinous for shipping companies and fatal for many open registries in small and developing nations. Shipowners, the foundation of global trade supplying the world would also have one more headwind to contend with at a time when capex demands increase in response to environmental regulation. This, combined with the added complexity of ascertaining exactly where shipping companies are domiciled, led to a heavily-lobbied-for exemption from the new tax rules. It appears the OECD and G7 appreciated this and that the present tonnage-tax system is advantageous for global trade stability. Furthermore, there are alternative ways to address low-tax jurisdictions.

For now, the new international tax regime has now rocked the boat, or those who own them, but the shipping industry touches many related industry sectors and definitional issues arising from the exemption could emerge. Prior to the OECD’s announcement of the deal, the ITF and Federation of European Private Port Companies and Terminals questioned why freight forwarders or port operators would pay the minimum global rate if their shipping company counterparts providing the same services were exempt. The result, they suggested, would be inadvertent market distortions and unfair tax competition would arise, which is precisely what the collective national effort sought to bring to an end. The exemption to the shipping industry calls for closer definitions of what “shipping” is, and until it is resolved, those involved in shipping services may find themselves thrust outside of the exemption’s scope and facing higher tax obligations.

For further information, please contact Adam Gray (a.gray@tamimi.com).

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.