Out from Under a Dark Cloud? Risks, Challenges and Evolution in Financial Crime Compliance Culture in the Middle East

Ibtissem Lassoued - Partner, Co-head of Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime - Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime / Family Business

Florence Jerome-Ball

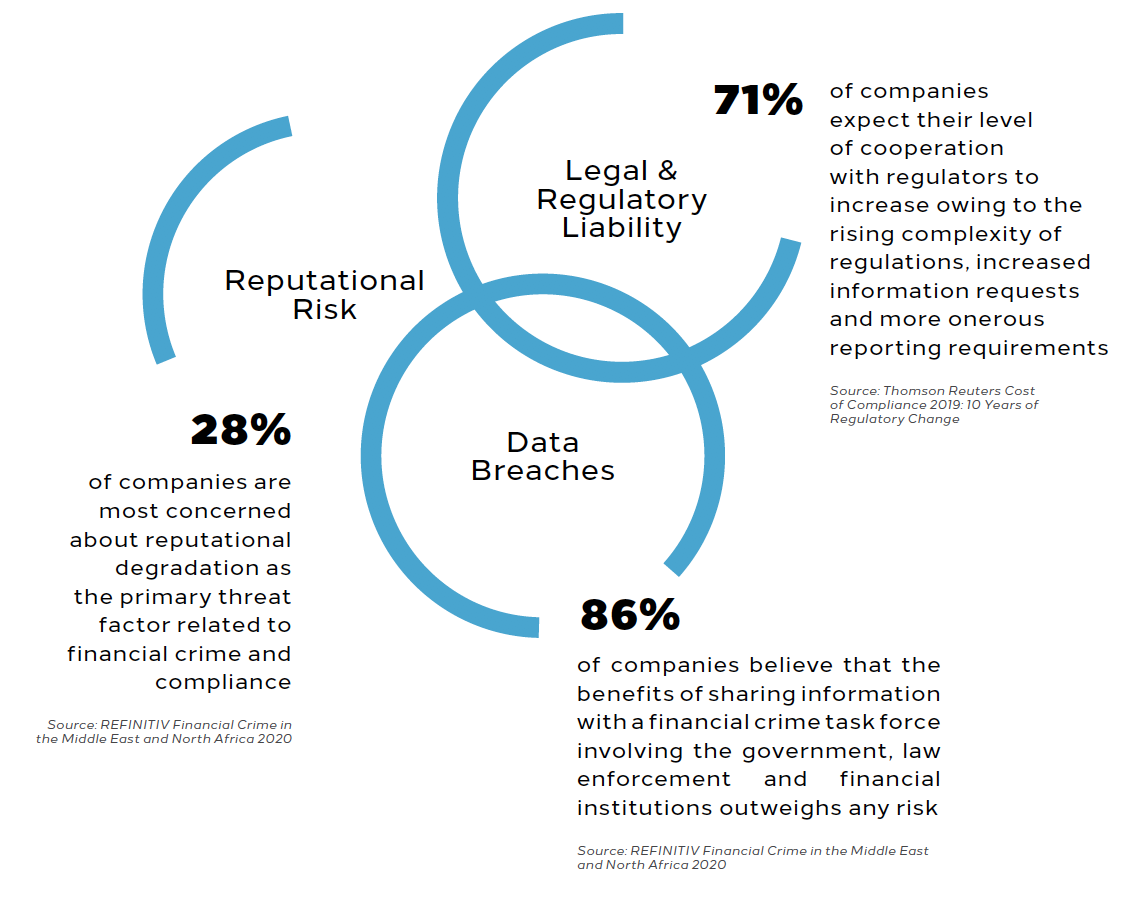

Attention devoted to compliance trends predominantly gathers around two main elements: cumulating costs, and abject failures. Statistics have charted a consistent rise in budgets dedicated to compliance operations in a trend that is not forecast to change any time soon. More than 55 per cent of companies report that their compliance budget is expected to increase by more than 25 per cent in the next 12 months1. In large part, the mounting costs are driven by amassing oversight requirements imposed to prevent financial crime, such as Know Your Client (‘KYC’) and Customer Due Diligence (‘CDD’) obligations imposed as part of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism (‘AML/CTF’) framework. Combined with stratospheric fines imposed for violations of various laws related to preventing illicit activity, businesses are faced with what can often seem like a dark dualism, with increasing legal and reputational risk matched to more arduous standards.

At the cutting edge of business culture, some changes are starting to clear the clouds, reversing the negative connotations attached to cost and risk heavy operations. After years of operating in the shadow of compliance expenses, companies are shifting their focus, assimilating sustainability and compliance objectives to turn compliance from a cost-centre to a revenue source. With the enhanced capabilities brought by data analytics and innovation, business service functions are, in some cases, able to spin positive value from the burdensome obligations imposed by various regulatory regimes and are investing in technology to automate procedures.

Whilst this is a positive development for companies seeking to update their compliance procedures, it is not yet the prevailing approach, and it will likely take some time before this will become a uniform approach for business across the Middle East. In the meantime, financial crime threats are insidious and severe, and authorities across the Middle East showcase a broad range of approaches to combat these issues. Whilst there is no monolithic approach that aligns regulatory development across the region, there are a number of indicators that identify local markets that are progressing towards standards that are more closely aligned with international best practice.

The approach of the authorities to sculpting the legal framework around financial crime issues informs the culture of compliance, creating a reinforcing, symbiotic relationship. The effectiveness of a legal framework is predicated on the extent to which compliance functions are able to implement the requirements, which lies at the heart of private sector participation in financial crime controls. The culture of compliance, and the risks and challenges faced in relation to key financial crime areas, is elemental to initiatives in eradicating illicit financing.

Stratified Standards

Mapping the underlying legislative drivers of compliance cultures across countries shows that standards are varied, as each jurisdiction exhibits its own approach to policing financial crime and unmatched pace of change. Cross-border dissimilitude amplifies risk for businesses operating in multiple countries, as uneven requirements create inconsistencies in controls.

In the Middle East, although each market exhibits diverse conditions and opportunities, there is a noticeable affinity in some areas that inform financial crime risk. In anti-money laundering reform, for example, the ongoing second round Mutual Evaluation assessments conducted by the Financial Action Task Force (‘FATF’) have drawn distinct parallels between the legislation of Gulf Cooperation Council (‘GCC’) that have recently been subject to assessment. Gulf countries have made a concerted effort in the time building up to FATF scrutiny to align their respective laws with the models of best practice, as prescribed by the international watchdog. In the UAE, implementation of Law No. 20 of 2018 (‘AML Law’) and the implementing regulations was accompanied by publication of extensive guidance by the authorities in an attempt to ensure the new provisions of the law were consistently interpreted and applied by private sector entities subject to the regulations. AML/CTF obligations form the cornerstone of financial crime controls and raising standards across the region are emblematic of the demands that will be placed on compliance functions aimed at detecting prohibited activities and gathering financial intelligence.

As these standards are raised, however, companies are forced to contend with increasingly complex obligations, which can inhibit effective implementation. Sanctions compliance represents a particularly nebulous area of restrictions, which is subject to constant change as overlapping listings change and the political agenda of implementing states diverge and combine intermittently. Recent AML legislation in several Middle Eastern countries has introduced new sanctions mechanisms intended to crystallise requirements, but there are still hurdles to clear before perfect implementation is realised. Awareness of domestic sanctions regimes and the potential applicability of international sanctions remains relatively low, and understanding of Ultimate Beneficial Ownership (‘UBO’) is not consistent. This crisis of confidence is pervasive; less than half of businesses have confidence in their compliance programmes and companies are increasingly looking to co-operate with supervisory bodies to share information on risks and appropriate counter measures.

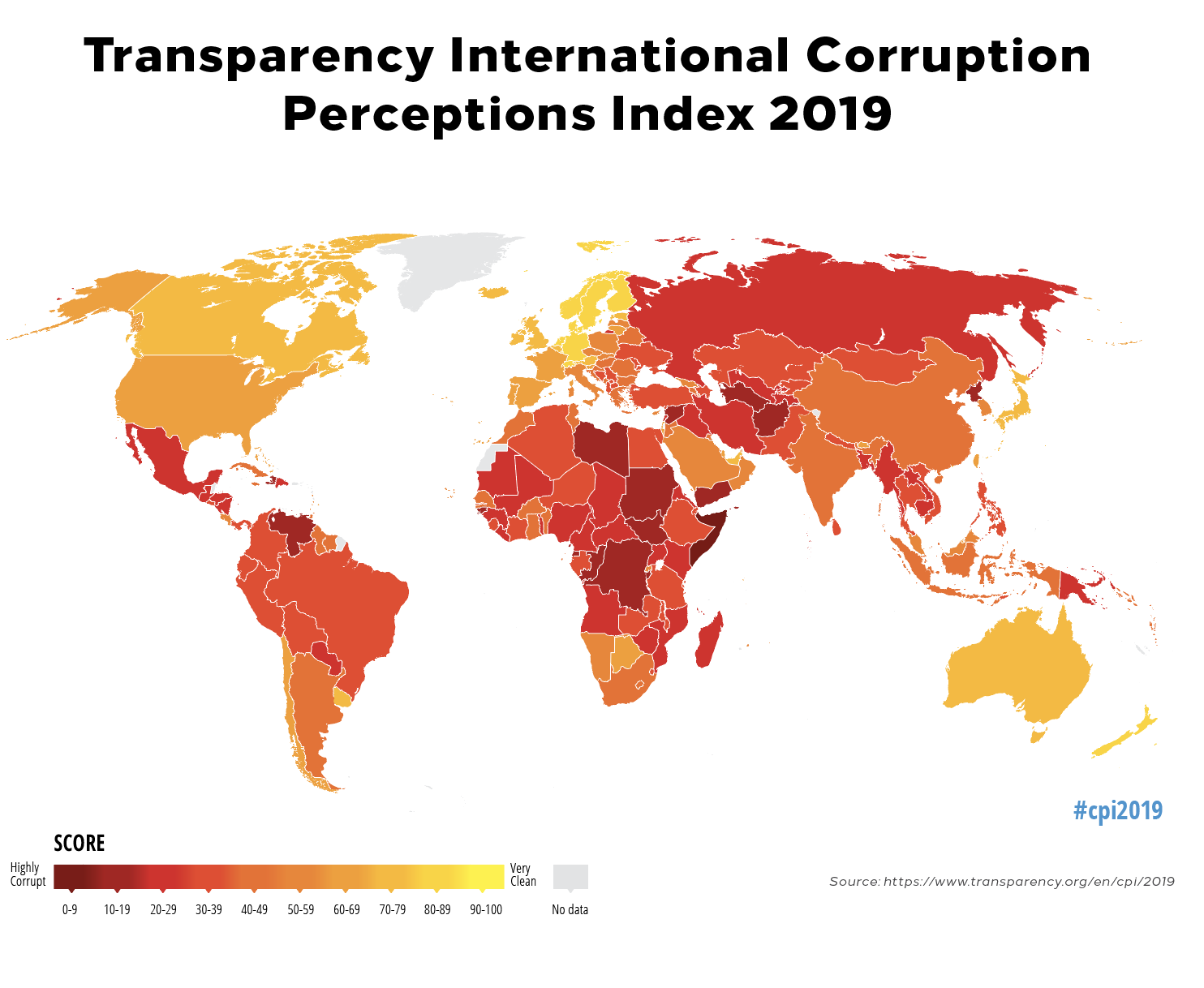

Corruption controls is another area that exemplifies the issues attached to differences in legislative tools, as the legal framework around bribery and corruption has transformed in piecemeal style across countries. Transparency International’s most recent Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 (‘CPI’), published in 2020, which is a leading measure for perceived corruption globally, indicates notable variations between corruption levels in the Middle East, which range from some of the worst scores in the world (concentrated around conflict zones) to levels like those in the UAE, which surpass even the US and some European countries with a score of 71. The CPI is not a ranking of regulatory conditions but, as an indicator of perceptions and experiences, it is useful in gauging how companies will assess their third-party risks in local jurisdictions and in turn how that may influence their approach to compliance measures. Businesses operating from international jurisdictions are looking to modify their internal compliance procedures in order to account for the increased risks posed by transacting with third parties in jurisdictions that do not have the same regulatory obligations. One of the most common devices used by international companies to protect themselves is the addition of contractual terms that mandate third parties to abide by their internal code of ethics and anti-corruption policies. Although this does not absolve the company of legal liability, it can be an effective way to mitigate against risk of illicit conduct.

Clouded Vision – Where Third Party Risks Thrive

Matching the trajectory of business development, third party risk is a frequently referenced escalatory concern for commercial entities. As economic expansion has fuelled the growth of companies, outsourcing and supply requirements have interlaced companies’ operations, creating chains of interdependent enterprises that are linked with a view to maximising capacity. Reliance on outsourced functioning can be a double-edged sword, however, increasing business amplitude but also exposing companies to risks caused by the conduct of external parties. In times where reputation is an invaluable asset to companies and scrutiny of operations is intensifying, this triad of contextual factors creates a deluge of considerations for companies when it comes to shoring up their compliance frameworks.

There are a multitude of risks that can rear up during the course of ordinary business with third parties, stemming from different sources. One of the primary difficulties is discrepancies in standards; whilst a company can expend great energy to ensure that its internal systems are watertight, any weaknesses in the defences of suppliers or consultants may spring a leak that causes irreparable damage. For example, in times of economic pressure, financial institutions may contract with external sales teams in an attempt to drive up their revenue, but these sales teams may lack sensitivity to the specific risks posed to the financial sector, unwittingly causing an influx of high-risk customers that may otherwise have been avoided by the financial institution. In other circumstances, contracting parties may be subject to a performance or target-based remuneration schemes, providing financial incentive for certain objectives that may come at the expense of compliance procedures. Increasingly, there are instances where companies are held liable for the actions of third parties where they are viewed to be acting in their capacity as ‘agents’. This situation can arise in various circumstances where the third party has been carrying out various functions, including sales and technical consultancy mandates, which only emphasises the need for businesses to balance their compliance and business objectives.

Aside from KYC and CDD measures which are the core of AML/CTF programmes, other financial crime risks require controls that are equally vulnerable to third party risks. With the digitalisation of many commercial activities and back office operations, cybercrime is a potent threat to both the bottom line and public standing of companies and consequently cybersecurity has assumed paramount importance. Where third party services require the transfer of customer data or other sensitive information, companies need to ensure that the security of the contractors is fit for purpose, or else risk leaving themselves exposed to potential hacking or data breach events. The rise in cybercrime is a well-publicised phenomenon, with the volume of funds and frequency of attacks often touted as a cautionary lesson for businesses that are keen to adopt technology but are not yet prepared to adequately defend their systems. As the increased incidence of cyberattacks becomes a more entrenched feature of the risk landscape, compliance requirements in this area are likely to ossify.

In recognition of the burdensome requirements of compliance under the UAE AML Law, the authorities have included provisions that allow regulated financial institutions and Designated Non-Financial Business and Professions (‘DNFBPs’) to outsource their CDD operations to third party service providers. This commercially sensitive approach by the UAE authorities has the potential to significantly improve the efficiency of compliance functions for regulated entities, however it also creates a paradoxical arrangement whereby companies attempting to reduce their third party risk by outsourcing due diligence may be held liable for the failures of the third party conducting its due diligence. Companies choosing to exercise this ability therefore need to proceed with extreme caution in vetting the service provider, as a lapse in judgment could have catastrophic consequences.

Despite the growing awareness of third party risks like those outlined above, models that implement macro level monitoring of risks and adjustment in compliance programmes are not yet commonplace. As the culture of compliance continues to evolve, practices in managing third party risk are likely to occupy central space in revised operating systems.

A Change in Direction

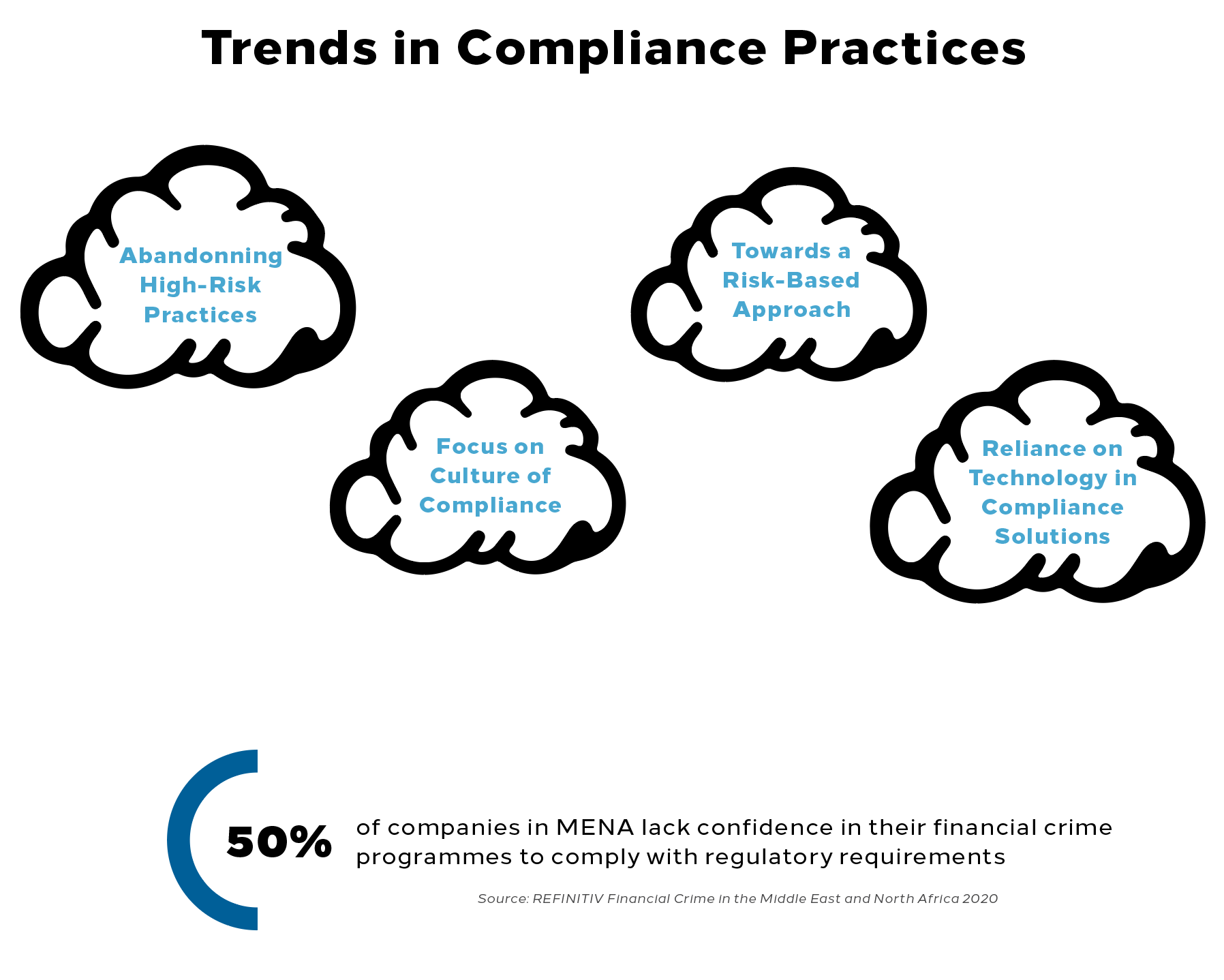

The interrelated dynamics of changing legal frameworks and shifting risks have begun to nudge compliance culture into more stringent practices. Increasing adoption of a risk-based approach means that compliance programmes are concentrated on high-risk activities, and astute business leaders are instilling a culture of compliance from the top to ensure consistent implementation.

Although KYC requirements may have become a recognised and routine part of business procedures for many companies, increasingly companies that work in high risk sectors or with high risk clients are deploying enhanced measures known as Know Your Client’s Client (‘KYCC’). In self-explanatory fashion, this involves vetting the client base of the business with whom a company is deliberating establishing a commercial relationship, and is a marked intensification of precautionary due diligence. KYCC measures are commonly seen in correspondent banking relationships, for example, where banks assume a certain degree of risk by consenting to act as a channel for funds from foreign banks.

Where reinforcement of controls is deemed insufficient, businesses are also abandoning high-risk practices, favouring risk avoidance over risk management. Practices such as using intermediaries or relationship consultants, which became notorious in certain circumstances for veiling schemes designed to gain illicit advantage, have diminished in use for regulated companies. In perhaps the most significant trend for compliance professions, ballooning investment is being sunk into advanced technological capacities that will ultimately automate the more basic elements of compliance procedures, thereby reducing both human error and practical expense. Other technological developments, such as the introduction of eKYC, also have the potential to dramatically change compliance processes.

Positive changes should be lauded, but there is still vast room for improvement. Data indicates that 51 per cent of external business relationships in the Middle East are not subject to due diligence at the onboarding phase3, indicative of fatal flaws in modern compliance practices. In light of all of these factors, compliance functions are going to continue to be at the centre of the maelstrom of financial crime risks, and it will be up to them to ensure that the right culture and policies are in place to allow them to manage the exposure and operations of the business. Businesses need to set a tone from the top that ensures that all directives are followed and a cohesive strategy is in place to monitor the development of risks. Notwithstanding the fact that failure to have a strong compliance culture may trigger investigations and legal cases, Middle Eastern companies that recognise the value of compliance programmes that adhere to international best practice, even where not required by local law, are more likely to be successful in engaging with international business partners that expect certain standards of conduct.

1Refinitiv Financial Crime in the Middle East and North Africa 2020

2Refinitiv Financial Crime in the Middle East and North Africa 2020

3Refinitiv Financial Crime in the Middle East and North Africa 2020

Artwork

Cloud pattern

Digital Creation

Variable dimensions

Curated by Rebia Naim @EmergingScene

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.