- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Real Estate & Construction and Hotels & Leisure

Real estate, construction, and hospitality are at the forefront of transformation across the Middle East – reshaping cities, driving investment, and demanding increasingly sophisticated legal frameworks.

In the June edition of Law Update, we take a closer look at the legal shifts influencing the sector – from Dubai’s new Real Estate Investment Funds Law and major reforms in Qatar, to Bahrain’s push toward digitalisation in property and timeshare regulation. We also explore practical issues around strata, zoning, joint ventures, and hotel management agreements that are critical to navigating today’s market.

As the landscape becomes more complex, understanding the legal dynamics behind these developments is key to making informed, strategic decisions.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- April 2020

- /

- COVID-19 and force majeure: UAE maritime law

COVID-19 and force majeure: UAE maritime law

Omar N. Omar - Partner, Head of Transport & Insurance - Insurance / Shipping, Aviation & Logistics

Gabriel Yuen - Associate, Transport, Trade & Logistics

![]() Following the spread of COVID-19, one of the main concerns UAE entities have been considering is whether contractual obligations could still be performed in light of various restrictions that have been imposed on transport and businesses alike. This article explores how the law of force majeure operates in the UAE and the legal considerations that parties in the maritime industry might take into account.

Following the spread of COVID-19, one of the main concerns UAE entities have been considering is whether contractual obligations could still be performed in light of various restrictions that have been imposed on transport and businesses alike. This article explores how the law of force majeure operates in the UAE and the legal considerations that parties in the maritime industry might take into account.

The starting point

Subject to public policy and statutory provisions, UAE law upholds parties’ freedom to contract. Most contracts include a force majeure clause, and where such clause is absent, contracting parties may fall back on Article 273 of UAE Federal Law No. 5 of 1985 (the ‘Civil Code’) to invoke force majeure:

1. ‘In contracts binding on both parties, if force majeure supervenes which makes the performance of the contract impossible, the corresponding obligation shall cease, and the contract shall be automatically cancelled.

2. In the case of partial impossibility, that part of the contract which is impossible shall be extinguished, and the same shall apply to temporary impossibility in continuing contracts, and in those two cases it shall be permissible for the obligee to cancel the contract provided that the obligor is so aware.’

Establishing force majeure

In essence, a force majeure is a supervening event rendering impossible the performance of an obligation under an agreement between parties. Whilst courts are not bound to follow the decisions of higher courts, judgments of the UAE’s highest court (the Court of Cassation) are typically followed. Therefore, it would be helpful to note that the Court of Cassation has, in two judgments, confirmed that force majeure must be unforeseeable and unavoidable: (Dubai Court of Cassation Judgment No. 101 of 2014 (Civil); and Dubai Court of Cassation Judgment No. 49 of 2014). It follows that a force majeure declaration is likely to fail if the underlying contract was entered into when public authorities have been imposing ever-stricter restrictions because it was foreseeable that that the obligation(s) would be impossible to perform.

Whilst it is good practice to specify what are force majeure events in an agreement, it is not necessary for the words ‘natural disaster’, ‘war’, ‘disease’, ‘pandemic’, ‘epidemic’ and the like to be expressly mentioned in a force majeure clause for force majeure to be successfully declared or argued in court. The key ingredient is impossibility of performance. Mere hardship, on its own, does not qualify as force majeure.

If force majeure under Article 273 of the Civil Code cannot be established, the doctrine of exceptional circumstances under Article 249 of the Civil Code may be an alternative. Unlike force majeure, which concerns impossibility, the doctrine of Exceptional Circumstances applies to excessively difficult obligations ‘threatening grave loss’. Further, unlike the consequence of successfully establishing force majeure (where the party declaring force majeure will not need to perform the relevant obligation), the party successfully establishing that exceptional circumstances took place would have its relevant obligation(s) adjusted to a level that the Court opines reasonable.

Force majeure under DIFC law

Under the laws of the Dubai International Financial Centre (‘DIFC’), force majeure is implied in Article 82 of DIFC Law No.6 of 2004. In any agreement governed by DIFC law, non-performance by a party is excusable if that party successfully proves that the non-performance was due to an event or incident beyond its control and that it could not reasonably have been expected to have taken the event or incident into account at the time of the execution of the contract, and thereby could not have avoided or overcome it or its consequences. However, a force majeure event will not excuse a party where its obligation is a ‘mere obligation to pay’.

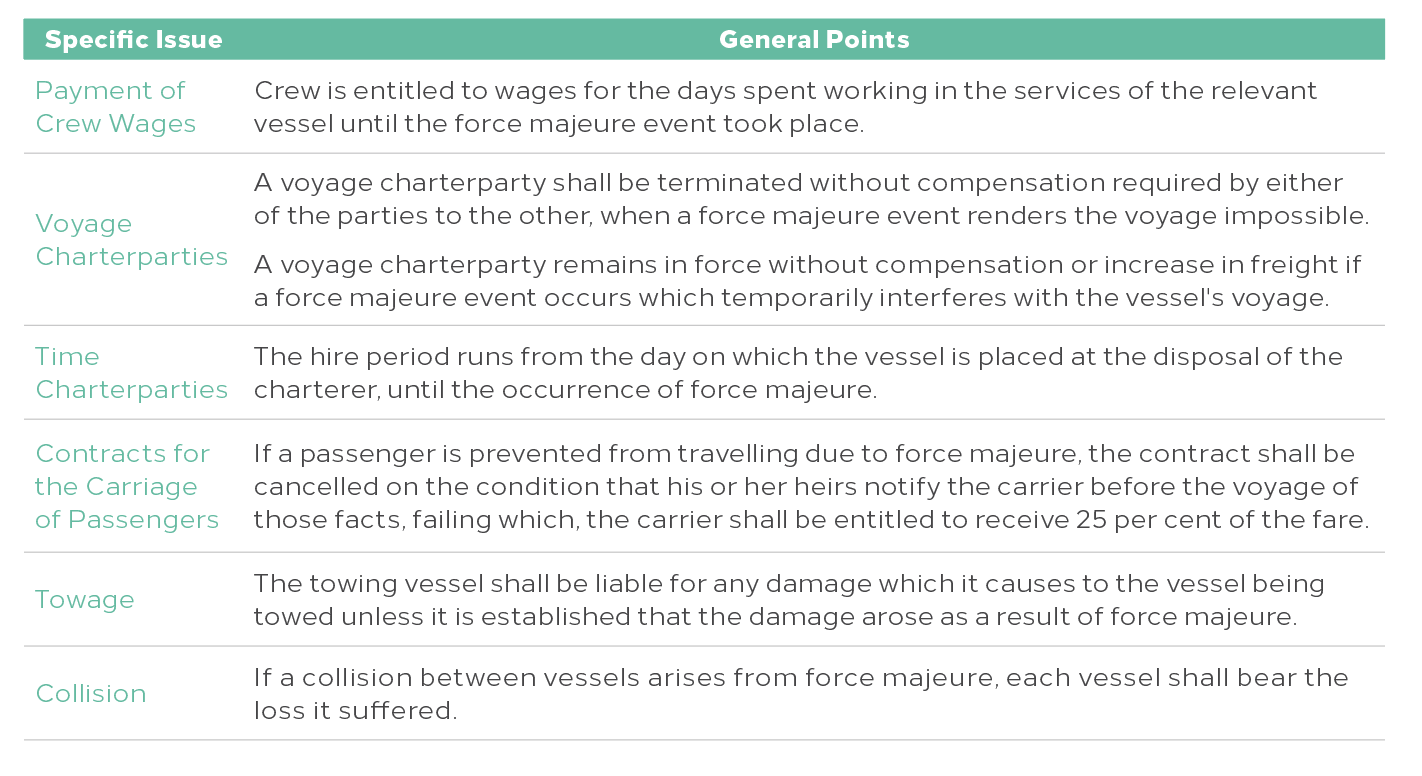

Maritime Specifics

Article 273 of the Civil Code, as discussed above, sets out how force majeure operates generally under UAE statutes, and that a successful declaration of force majeure may result in cancellation of contracts. However, UAE Federal Law No. 26 of 1981 further specifies certain rights and liabilities of parties in maritime and shipping scenarios concerning force majeure, of which the latter parties should be aware.

Going forward

Despite the ongoing restrictions faced by parties in the maritime and logistics sectors, many transactions and operations in these sectors are still continuing. Due to the evolving circumstances, it is suggested that the following be considered in order to stay ahead of the potential hurdles and hiccups:

- review your agreements and determine whether the force majeure clause specifies epidemics, pandemics, disease and the like as force majeure events;

- consider how notice is performed as stated in your contracts, or if there are specific requirements for declaring force majeure;

- if you intend to declare force majeure, consider how any of your losses may be mitigated and or reduced, and do so without delay;

- familiarise yourself with your insurance policies and claim-making processes;

- concerning ‘Safe Port’ obligations under charterparties, determine whether the load and discharge ports that your vessel calls, have implemented procedures to ensure safety of persons and crew;

- review your charterparties’ Deviation Clause to confirm the right to deviate from agreed route(s), and whether freight and hire clauses were drafted in your favour in situations such as deviation; and

- in Ship Sale & Purchase transactions, buyers should ensure sellers of ships obtain necessary permits from the respective port for the ship to leave following delivery or closing.

For further information, please contact Omar Omar (o.omar@tamimi.com) or Gabriel Yuen (g.yuen@tamimi.com).

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.