A Green Light to Prosecute: Lessons Learned from the Omani Ministry of Education Embezzlement Case

Khalid Al Hamrani - Partner, Co-head of Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime. - Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime / Family Business

Wassim Mahmoud

Following in the footsteps of its neighbours in the Gulf, Oman has not been idle in recognising the insidious nature of corruption, and has acted to limit its impact. Oman has ratified the United Nations Convention Against Corruption through Sultani Decree Number (64/2013), and has openly stated its ambition to fight and eliminate corruption. Whilst political statements and sweeping legislation create an impression of high-level progress, examining corruption cases that make their way through the Courts is invaluable in understanding how these issues manifest at the ground level.

One such demonstrative case has garnered considerable public interest in Oman as it concerns public funds and corruption. The case, which has become known as the ‘Ministry of Education Embezzlement Case’ is considered to be a test case and an indicative precedent as to how the governmental and judicial authorities will deal with such corruption matters.

By chronicling the investigative measures, criminal procedures and approach applied by the Omani authorities in this case, it is possible to gain an insight into how public corruption cases will be treated by law enforcement authorities and the judicial system in future.

Breaking News

Public awareness of the case was first provoked in March 2019, when a flurry of social media activity spread news of the arrest of public employees at the Ministry of Education (‘MoE’) on charges of embezzlement for an amount in the millions of Omani Riyals. The news was confirmed by official sources on 27 March, by Oman Government Communication Centre (‘Centre’).

The Centre affirmed that the authorities were expending all possible efforts in compliance with the relevant legal procedures to pursue justice against the perpetrators. Pursuant to the Conflict of Interests Law, promulgated by Sultani Decree Number (112/2011) and the Oman Penal Code, promulgated by Sultani Decree Number (7/2018), the Public Prosecution was the competent authority for conducting investigative procedures in co-operation with the State Audit Institution and the MoE.

Investigation

The Public Prosecution initiated its investigation by interrogating the suspects in the case in accordance with criminal procedures, and also collected and verified documentary evidence. The suspects were confronted with forged documents bearing their signatures, alongside various other evidence collected by the State Audit Institution and presented by the Public Prosecution. Accordingly, the suspects were arrested and, on completion of all necessary further formalities and investigations, were referred to the Competent Court for trial. In June 2019, the Public Prosecutor declared that the case had been referred to the Competent Court and that hearings would commence imminently.

Generally, in other investigations, the State Audit Institution and the Public Prosecution Office work to obtain information about other, as yet unidentified, collaborators potentially increasing the circle of suspects who might have played a role in a single offence. Additional suspects may be joined as parties to existing proceedings, or new legal proceedings will be initiated against them. This type of information may not be accessible or become known until the interrogation and investigation of the accused takes place.

Legal Proceedings

On 7 July 2019, the first hearing session was held at Muscat Criminal Court where a total of 18 individuals (15 employees from the MoE and three other accused from other authorities) were announced as official suspects in the case.

During the hearing session held on 9, September 2019, the Public Prosecutor displayed the audit report of the State Audit Institution, which demonstrated that one of the suspects issued 256 cheques in total, that were cashed in the name of the MoE, to provide school supplies and bonuses without any legal basis for such payments.

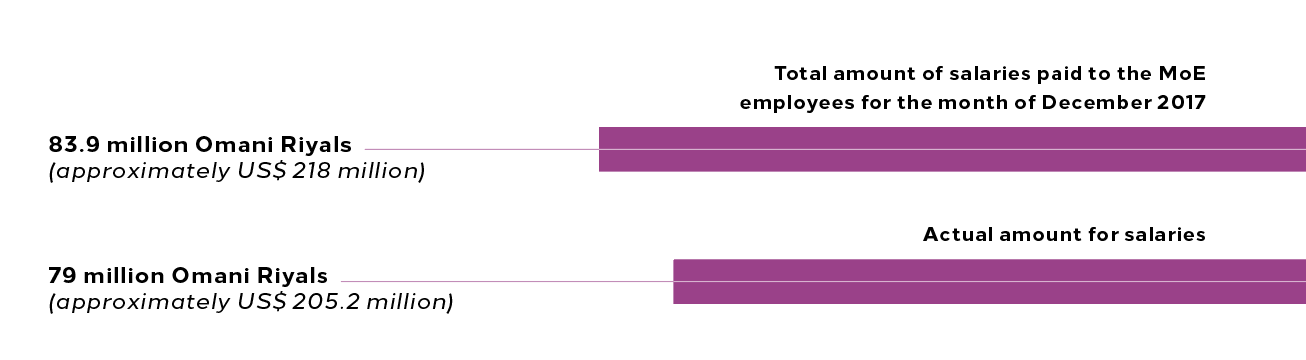

The Public Prosecutor submitted that in the year 2017, a total amount of seven million Omani Riyals (approximately US$ 18.2 million) was embezzled by way of issuing fake exchange bonds without any legal support, nor obtaining the requisite internal audit approvals. In addition, the Public Prosecutor revealed, in its assertions that the total amount of salaries paid to the MoE employees for the month of December 2017, amounted to 83.9 million Omani Riyals (approximately US$ 218 million). It was established that the actual amount for salaries for that period should have been only 79 million Omani Riyals (approximately US$ 205.2 million), which was considered to prove, beyond any doubt, that embezzlement had occurred. Moreover, the Public Prosecutor illustrated that the suspects had attempted to conceal the origins of the funds unduly gained through embezzlement by routing them through banking transfers and commercial transactions such as buying shares in international companies and purchasing real estate and vehicles, both within Oman and in other jurisdictions. This was done with the co-operation of other individuals that did not work in the MoE. In attempting to disguise the source of funds in this way, the suspects had committed a further crime of money laundering. On the basis of the evidence obtained during the investigation, the Public Prosecutor indicted all the suspects and accused them of different crimes including intentional negligence, fraud, embezzlement with forgery, money-laundering, electronic fraud, and abuse of public office.

As is common practice in such cases, the Omani government takes precautionary measures before making any allegations against public officials. During the investigation stage, enquiries into the funds and assets of suspects that are located inside or outside Oman are treated as a priority, so that confiscation can be accelerated once legal proceedings are initiated. As a result, it is expected that in most circumstances, unless public officials suspected of committing corruption offences are able to mount a convincing defence, a more favourable judgment will be issued in favour of the government or one of its bodies so it can recover its losses and its functioning is not compromised. The period of imprisonment and the level of fines applied by the Court would depend largely on the severity of each offence and its classification, and would be decided at the discretion of the Judge.

By leveraging a range of offences provided by the Penal Code, the Public Prosecutor was able to increase the extent of criminal sanctions that could be applied by the Courts in the event of a conviction. The Public Prosecutor called for the imposition of severe penalties against the suspects, to include imprisonment and dismissal from public employment, the confiscation of all real estate and amounts obtained by the suspects resulting from the embezzlement, the confiscation of all financial profits accruing from the money laundering process as well as the confiscation of any other private property, registered in the names of the suspects, equivalent to the amount of money obtained by embezzlement and money laundering.

Ruling

On 1 December 2019, the Muscat Criminal Court issued its verdict. The sanctions varied from one suspect to another, depending on the offence in question and the extent of their involvement in and benefit from the embezzlement scheme. The first and second accused, as the predominant perpetrators, were sentenced to 25 years (with a minimum of 20 years) imprisonment, respectively. The Court also sentenced eight of the accused to a prison term ranging between one to ten years, while it imposed a fine of 100 Omani Riyals (approximately US$ 260) for six of the accused as a sanction for intentional negligence, although it declared their innocence of the charge of misusing public funds. Two of the accused were acquitted.

In addition to imprisonment, the Court made restitution a legal obligation and a part of the total penalty for embezzlement and misappropriation of public funds. This is in adherence to the new principles stated in the Omani Penal Code, which entered into force on 11 January 2018 by the Royal Decree No 7/2018. Those found guilty were ordered by the Court to compensate the MoE for its losses caused through the commission of the offences. Commensurate to the losses suffered by the MoE, the Court ordered the accused to pay fines amounting to more than 15 million Omani Riyals (approximately US$ 39 million) and ordered confiscation of any other private property, registered under their names, equivalent to the amount of money obtained as a result of the embezzlement and money laundering. As a further means to protect against the future commission of such offences, and to demonstrate the severity of the conduct in question, the Court further ruled that certain guilty parties be dismissed from public service for life.

Lessons Learned from the MoE Case

With the issuance of the new Omani Penal Code, particular importance has been attributed to financial crimes in public office and the financial sector as is reflected in the severity of the penalties that can now be applied to any employee or public official that abuses their position or function in order to achieve personal benefit. The imposition of elevated penalties is a well-recognised legislative tool that is deployed in countries all over the world to deter individuals, in both the public and private sectors, from committing acts that may compromise the integrity of the economic system. Financial crime offences have substantial impact on commercial activities, undermining the security of transactions and the development of the economy and society in general.

Chapter IV of the Penal Code focuses on offences committed by public officials that cause damage to public funds. The purpose of the provisions is to provide a framework of rules aimed at enhancing transparency within the public sector. The newly introduced provisions criminalise embezzlement, misappropriation of public funds, illegitimate collection of taxes, fees or fines, causing wilful damage to public property, neglecting the maintenance of public property, trickery relating to public bids or auctions, receiving illegitimate profit or benefit, obtaining illegitimate benefits based on Government contracts, fraud in the performance of Government contracts, and trespass to Government property.

Drawing together the breadth of these offences and the strength of the penalties which they attract, the Omani Penal Code constitutes a qualitative leap in legislation in the Sultanate. It specifically targets financial crime offences that carry damaging effects and ramifications for the Omani system and, in so doing, supports the efforts of the Omani authorities to construe the country as an attractive and safe destination for foreign investment, where business interests are protected by strong rule of law and governmental integrity.

Taking Notes for the Future

With the fall in oil prices and the persistence of the COVID-19 pandemic creating economic pressure in Oman, public funds have amassed, if anything, even greater importance to the continued economic and social health of the Sultanate. As such, the government is likely to take a strict approach to dealing with officials who have abused their powers and misappropriated public funds, taking into consideration the fact that there is no time limitation as to when the Government or one of its bodies may claim such right. This may take the form of an internal investigation into suspected officials, or even freezing of their assets prior to the referral of any allegations to the Courts. The MoE Embezzlement Case has thrown the potential of further similar cases into stark relief.

In this light, fighting corruption has become a necessity in order to further strengthen the position of public institutions in Oman, bolstering the country’s resilience in managing public funds and assets, and ultimately improving its ability to deal with any crises that may arise. Misappropriation of public funds, or any other offences relating to public interest, may immobilise the ability of the Government to maintain its financial obligations both internally towards its employees and designated function, and/or externally towards any third parties under contract and the public at large.

This latter category has proven to be a particular area of concern. Most existing cases of offences relating to public funds arise out of or in connection with contracts or sub-contracts with governmental bodies, and as such the Omani government is likely to tighten its policies and legislation regarding the process of public procurement and the budget allocated for such projects. In the context of the current economy, the Government will need to make sure that it can strike a balance between controlling public procurement without stifling the flow of public funds to the economy, which may carry a risk of forcing the closure of existing contractors and sub-contractors and causing job losses for Omani and non-Omani employees. As evidenced by the MoE Embezzlement Case, the Omani authorities have struck a strong tone in their approach to prosecuting crimes against public funds, but they will need to ensure that this continues to resonate as the needs of the economy are shaped by the status of the international pandemic.

Aurora

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 60 cm

Curated by Rebia Naim @EmergingScene

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.