- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Real Estate & Construction and Hotels & Leisure

Real estate, construction, and hospitality are at the forefront of transformation across the Middle East – reshaping cities, driving investment, and demanding increasingly sophisticated legal frameworks.

In the June edition of Law Update, we take a closer look at the legal shifts influencing the sector – from Dubai’s new Real Estate Investment Funds Law and major reforms in Qatar, to Bahrain’s push toward digitalisation in property and timeshare regulation. We also explore practical issues around strata, zoning, joint ventures, and hotel management agreements that are critical to navigating today’s market.

As the landscape becomes more complex, understanding the legal dynamics behind these developments is key to making informed, strategic decisions.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- October 2019

- /

- Mediation in the Middle East: Before and After the Singapore Convention

Mediation in the Middle East: Before and After the Singapore Convention

Sara Koleilat-Aranjo - Partner, Arbitration - Arbitration / Litigation / Mediation

Aishwarya Nair

N.B. An edited version of this article has been previously published on the Kluwer Mediation Blog.

N.B. An edited version of this article has been previously published on the Kluwer Mediation Blog.

The United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, known as the Singapore Convention on Mediation (the ‘Singapore Convention’), was opened for signature on 7 August 2019. The Singapore Convention already boasts 46 signatories. Of these 46 nations, five belong to the Middle East. At first sight, and when compared to the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958) (the ‘New York Convention’) in absolute numbers of Middle Eastern signatories, it would appear that the Singapore Convention may not have been as warmly received as the New York Convention (with a total of 13 Middle Eastern signatories). However, on a closer look, and when compared on the basis of the number of Middle Eastern signatories at the time of its launch (only Jordan from the Middle East signed the New York Convention on 10 June, 1958), the prospects of the Singapore Convention in the region instantly seem brighter.

In this article, we aim to provide a vignette of mediation practice across the Middle East and highlight the prospects of its continued development in the region in light of the Singapore Convention, after discussing some of the key highlights of this international law instrument.

Selected Highlights of the Singapore Convention

The Singapore Convention has been hailed as the “missing piece” in the international dispute resolution enforcement framework. It establishes a framework for the cross-border recognition and enforcement of settlement agreements (Article 3 of the Singapore Convention) and aims to bring predictability and stability to the international framework on mediation. Noteworthy provisions of the Singapore Convention include:

1. Clearly Defined Scope of Application

Article 1(3) of the Singapore Convention precludes settlement agreements that are enforceable as court judgments or arbitral awards from its application. This has created a well defined field for the exercise of this Convention and eliminates potential overlaps with other conventions regulating international trade such as the New York Convention and the Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements (2005).

While the New York Convention will continue to govern settlements achieved through mediation that is part of Med-Arb and Arb-Med-Arb processes, the Singapore Convention now grants an equal level of authority to settlements solely resulting from mediation. Indirectly therefore, this will help establish mediation as an independent and more effective means of Alternative Dispute Resolution (‘ADR’), as opposed to a subsidiary step in the arbitration process.

2. Procedural Safeguards

Articles 5(1)(e) and (f) of the Singapore Convention provide that the competent authority may refuse relief on the grounds of “serious breach of standards applicable to the mediator or the mediation” and failure to disclose “circumstances that raise justifiable doubts as to the mediator’s impartiality or independence”.

Interestingly, the Singapore Convention does not stipulate the standards that are to be used to assess the conduct of the mediation, the mediator or the latter’s impartiality. According to the Travaux Préparatoires, it was noted that “the competent authority [would be allowed] to determine the standards applicable, which could take different forms such as the law governing conciliation and codes of conduct, including those developed by professional association” and further stated that “the text accompanying the instrument would provide an illustrative list of examples of such standards.”

As the Singapore Convention does not set out any illustrations for either provision, and since there is no soft law or guidance on which States may rely (unlike arbitration, mediation receives scant attention from international associations; a quick scan of the International Bar Association Committee web pages for arbitration and mediation is enough to arrive at this conclusion), the onus for clarifying these standards now lies with the competent authorities in each ratifying State.

Consequently, and where required, signatory States will have to include standards within their own national laws before they will be able to ratify the Singapore Convention. In turn, this may spur the production of soft law instruments to streamline and harmonise these standards. As a result, there is sure to be the creation of standards so far elusive in mediation aside from the generation of greater awareness and discussion of mediation in the visible future. It is worth noting that at present, the recently launched Saudi Centre for Commercial Arbitration (‘SCCA’) provides a code of ethics for mediators in Saudi Arabia.

Mediation in the Middle East: In Retrospect

Mediation (‘al-Wasata’) has historically been an integral element of the traditional structure of dispute resolution in the Middle East. While it has been popular as an informal means of settling commercial disputes, recently, there have also been continuous developments in commercial mediation in the region.

For example, in the United Arab Emirates (‘UAE’), agreements resulting from mediation have been enforceable through certain avenues for some time now. Federal Law No 26 of 1999 Concerning the Establishment of Conciliation and Arbitration Committees at Federal Courts established conciliation and reconciliation committees at the Federal Courts for facilitating the settlement of civil, commercial and labour disputes. Any settlement reached through the committees is embodied in a court document and treated as a writ of execution.

Similarly, the Centre for Amicable Settlement of Disputes in Dubai was established pursuant to Dubai Law No. 16 of 2009 Establishing a Centre for Amicable Settlement of Disputes. The Centre is associated with the Courts and is tasked with attempting to mediate disputes before they are referred to the Courts. Any settlement agreement arrived at is legally enforceable and is equivalent to an executive instrument which may be directly enforced through the Execution Courts.

Jordan passed the Mediation in Resolving Civil Disputes Act in 2006. This paved the way for a standalone regime for court-based mediation; mediations were subject to time constraints (they had to be completed within three months) and the settlements arising out of them were final. Private mediations were also recognised but were not privy to the enforcement mechanisms that are available to court-based mediations.

Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, the SCCA which was set up in 2016 provides both arbitration and mediation services. With regard to mediation, the Centre has developed rules closely modelled on the ICDR-AAA Rules apart from the aforementioned code of ethics for mediators. In December last year, the Ministry of Justice also organised an advanced training programme for qualifying court mediators on best practices to settle disputes following international standards.

In Qatar, the Qatar International Center for Conciliation and Arbitration (‘QICCA’) was established in 2006 and adopted a set of Conciliation Rules in May 2012 (the’ QICCA Conciliation Rules’), which were modelled on the UNCITRAL Conciliation Rules. The Qatar International Court and Dispute Resolution Centre (‘QICDRC’) has also been providing mediation services in partnership with the Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution (‘CEDR’) since 2010.

As it stands currently, and within the Arabic States, the Singapore Convention has been signed by Jordan, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. This leaves behind established centres of ADR in the region like the UAE as well as growing centres such as Egypt, Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon and Oman. This is not to say however that significant changes are not already underway in these countries.

In Bahrain, the Bahrain Chamber for Dispute Resolution (‘BCDR-AAA’), an independent dispute-settlement institution in operation from 2010, has been offering mediation services to commercial and governmental parties in the region. In July this year, the Mediation Rules were updated to coincide with the signing of the Singapore Convention. Most notable, amongst the changes, are the updated provisions on independence and impartiality and the option for parties to commence or continue parallel arbitral or judicial proceedings.

Within the last year, the following three countries have seen major changes to their mediation frameworks. In Lebanon, Law No. 82, was published in the Official Gazette on 18 October 2018. This law, which entered into force in May 2019, enables parties to access mediation once their dispute is submitted to the court, at any time during the court proceedings. This will supplement the Lebanese Arbitration and Mediation Center (‘LAMC’) that already provides mediation services. In Oman, the Oman Commercial Arbitration Centre (‘OCAC’) was launched in July this year. At the press conference, an OCAC Board Member noted that the Centre would include mediation services as part of its competencies. Around the same time in the UAE, the Abu Dhabi Global Market (‘ADGM’) Courts announced the launch of their court-annexed mediation service for ADGM entities and litigants before the ADGM Courts. This brings the ADGM Courts on par with the other offshore jurisdiction in the UAE – the Dubai International Financial Centre (‘DIFC’), where the DIFC Courts include mediation in certain procedures and promote mediation as an alternative means of resolving disputes (the DIFC-LCIA Arbitration Centre also offers mediation services to users modelled on the LCIA Mediation Rules).

Mediation in the Middle East: Prospects

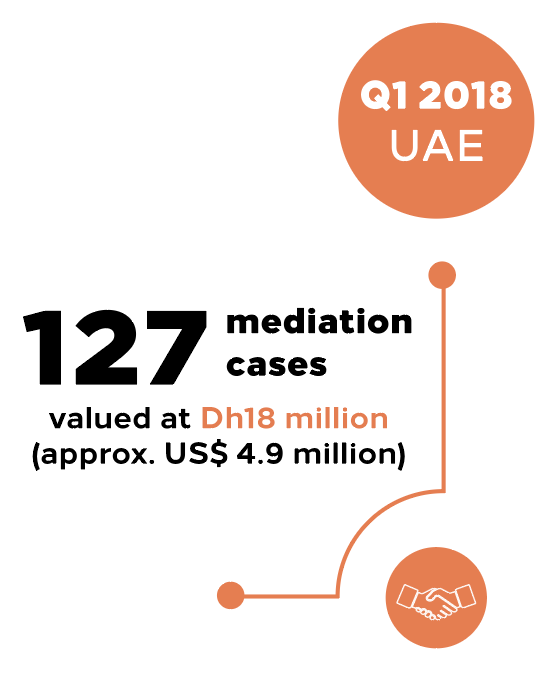

As underlined at the start of this article, the initial reception of the Singapore Convention in the Middle East is to not to be deemed as indicative of its ultimate success. Since State parties may accede at any stage to the Singapore Convention it is, more than likely, that the nations in the Middle East that have not yet signed the Singapore Convention will soon follow in the path of their peers that have signed the Singapore Convention to keep up with the rising demand for mediation in the region. For example, in the UAE alone, the Dubai International Arbitration Centre (‘DIAC’), which sits under the umbrella of the Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry, reported 127 mediation cases valued at Dh18 million (approximately US$ 4.9 million) in the first quarter of 2018. \

With the need to bring their national laws in line with their obligations under the Singapore Convention, signatories in the region will have to amend or, as in most cases, introduce dedicated standalone national laws on mediation. While there is much that remains in the air with regard to how effectively, and through what strategies, each of these countries will implement the Singapore Convention in their jurisdictions, one thing that we know for certain is that mediation in the Middle East is in for a facelift with a view of a promising future.

Al Tamimi & Company’s Dispute Resolution team has the capability to provide advice to clients on mediation proceedings, to assist as counsel in mediations and to act as mediators in commercial disputes across the region. For further information, please contact Sara Koleilat-Aranjo (s.aranjo@tamimi.com).

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.