- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Real Estate & Construction and Hotels & Leisure

Real estate, construction, and hospitality are at the forefront of transformation across the Middle East – reshaping cities, driving investment, and demanding increasingly sophisticated legal frameworks.

In the June edition of Law Update, we take a closer look at the legal shifts influencing the sector – from Dubai’s new Real Estate Investment Funds Law and major reforms in Qatar, to Bahrain’s push toward digitalisation in property and timeshare regulation. We also explore practical issues around strata, zoning, joint ventures, and hotel management agreements that are critical to navigating today’s market.

As the landscape becomes more complex, understanding the legal dynamics behind these developments is key to making informed, strategic decisions.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- April 2020

- /

- Coronavirus: hotel management agreements and force majeure

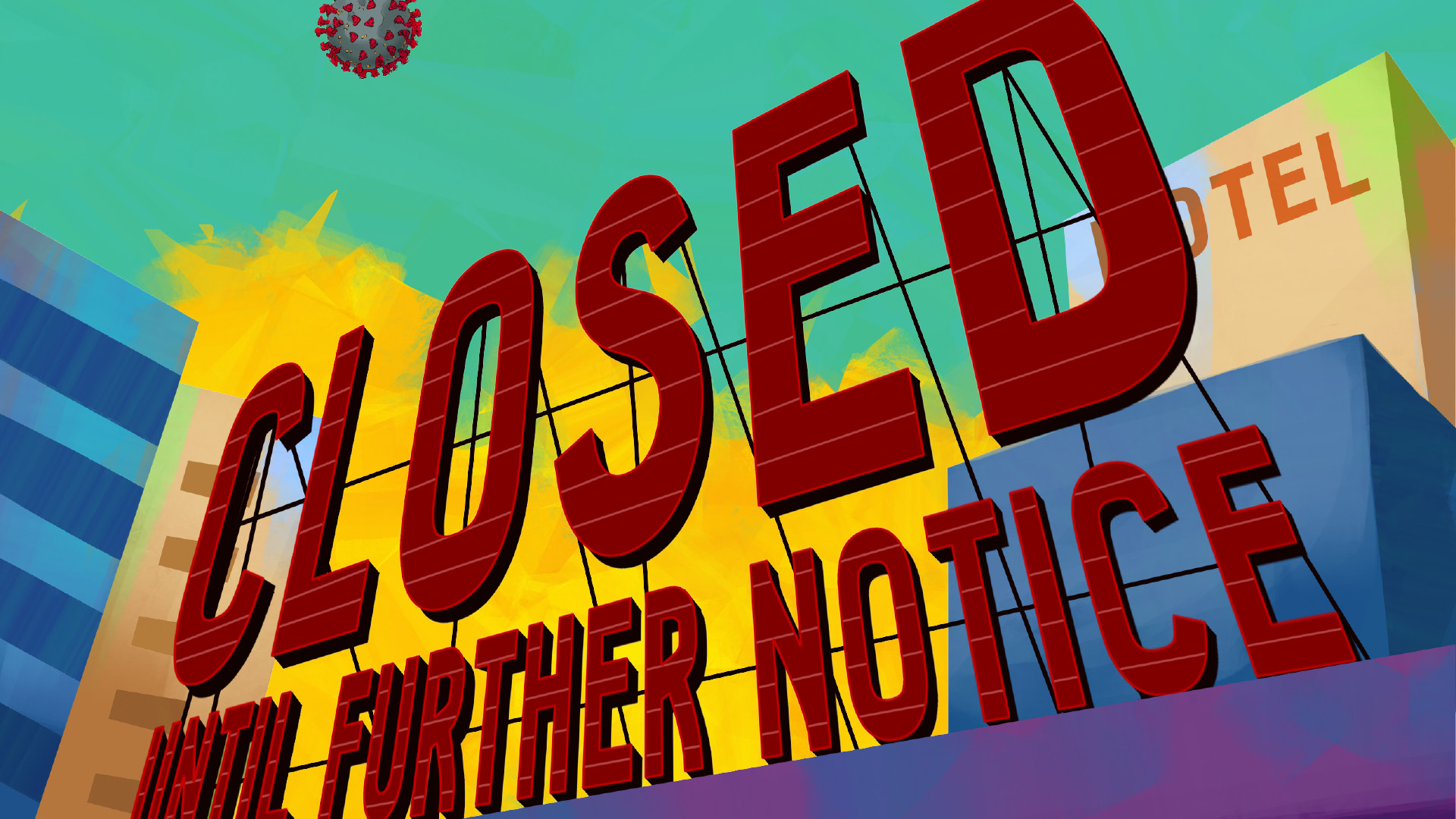

Coronavirus: hotel management agreements and force majeure

- Head of Hospitality Development

![]() The tourism and travel sectors are currently at the forefront of disruption caused by the global outbreak of Coronavirus (‘COVID-19’) with hotel revenues significantly impacted both regionally and globally.

The tourism and travel sectors are currently at the forefront of disruption caused by the global outbreak of Coronavirus (‘COVID-19’) with hotel revenues significantly impacted both regionally and globally.

There was already tension in the UAE hotel market impacting both owners and operators with decreased occupation, room rates and revenues and owners experiencing difficulties in servicing their debt obligations. The Coronavirus pandemic and the resulting economic fallout seems likely to exacerbate such tensions.

Travel restrictions implemented globally to reduce the spread of the virus have all but put tourism in the UAE completely on hold for the near future. Many hotels have taken the decision to close for the time being. For those hotels that remain open, occupancy is at unprecedentedly low levels resulting in such hotels taking urgent steps to reduce their operating expenses, such as placing staff on unpaid leave, reassessing suppliers of goods and services and closing off room inventory where not required to accommodate guests. Below we look at some of the legal ramifications:

Performance tests

In the region, the relationship between hotel owners and operators is most commonly governed by a hotel management agreement (‘HMA’). Most HMAs include a performance test whereby a hotel owner may terminate the HMA (or receive a cure payment covering some of the profit shortfall) if the hotel’s performance fails certain performance related tests. A typical performance test involves the operator needing to ensure that both:

- the actual Gross Operating Profit (‘GOP’) of the hotel achieves a certain agreed percentage of GOP as compared to that determined or agreed in the annual budget (‘GOP Test’); and

- the Revenue Per Available Room (‘RevPAR’) achieves a certain agreed percentage of the average RevPAR of an agreed ‘Competitive Set’ of comparable hotels in the local market (‘RevPAR Test’).

Such tests usually need to be failed over a number of consecutive financial years (two years is typical) before the owner’s rights are triggered.

However, a performance test clause will usually contain certain circumstances whereby the hotel is deemed to have satisfied the test despite having not met the relevant performance targets. Force majeure is one of such events that is typically carved out.

Whether or not a performance test failure can be avoided due to the effects of the pandemic will depend upon how ‘Force Majeure’ has been defined in the HMA and the position under the relevant governing law of the agreement (for example, many HMAs in the region are subject to the laws of England & Wales rather than the jurisdiction in which the relevant hotel is located) . Although force majeure definitions usually contain general sweep-up wording that covers all events outside of the reasonable control of the contractual parties, for the sake of certainty, operators will often seek to expressly reference such matters as local, regional or global outbreaks of infectious disease, epidemics or pandemics, and travel disruption affecting the country in which the hotel is located, as specific events of force majeure. Operators may also seek to extend the scope of the force majeure definition to overseas territories if its sales and distribution platforms have a large reach and a customer base in particular countries. This is so that those source markets for guests that provide a significant part of the hotel’s revenue are included and events such as travel restrictions being imposed upon, or even a general economic downturn in, such key target markets are included as events of force majeure. As the force majeure definition is key to the performance test, a hotel owner will often seek to limit its scope through localising the definition to just cover relevant events that occur within the country in which the hotel is located (with general market and economic conditions also expressly excluded).

The HMA should also be closely examined regarding how the force majeure carve-out operates specifically in relation to the performance test. For example, if a force majeure event and its likely effect on revenue and profit is within the knowledge of the operator at the time that the annual budget is agreed or determined, then there may be wording included preventing such event from being relied upon to neutralise the GOP Test, as such matters should have been taken into consideration at such time.

Also, in relation to the RevPAR Test, there may be wording whereby force majeure may not be relied upon to the extent that it also generally affects the other hotels in the Competitive Set (as RevPAR is likely to be affected in a similar way for all of such hotels). For example, if the pandemic has generally reduced RevPAR across the Competitive Set, the hotel’s percentage target will be similarly reduced and it is unlikely that the hotel would, in such circumstances, fail the RevPAR test (as the other hotels in the Competitive Set would be similarly impacted). However, if this is not the case and the hotel has failed the RevPAR test, then reliance on the event of force majeure (i.e. the pandemic) as a direct cause for the failure would, if challenged, need to be proved.

However, if for example, the hotel was shut down due to a specific outbreak at the hotel, it would be reasonable to allow this as a direct cause of the failure of the RevPAR test.

The effect of one or more of the hotels in the Competitive Set being closed would also need to be considered in the context of the relevant HMA provisions.

Generally, given the current unprecedented and extreme circumstances, we consider that it would be very difficult for an hotel owner to claim a failure of the performance test for the current financial year.

Construction milestones

For those HMAs entered into between owner and operator prior to or during construction (which remains the most common form of HMA in the region), the owner is obligated to comply with various milestone dates, usually relating to construction commencement, completion and hotel opening, which, if not met, places the owner at risk of termination by the operator. However, events of force majeure usually allow for the relevant milestone date to be extended up to a maximum long stop date. Supply chain issues caused by the pandemic are having a palpable effect on construction timelines. Owners should therefore review the force majeure clauses in their HMAs if it is likely that such construction delays could potentially place the owner in breach and at risk of termination.

General force majeure provisions

HMAs also usually contain a general force majeure clause whereby one of the parties is relieved from its obligations and not in breach where such performance is prevented due to an event of force majeure. These vary in nature. Sometimes they just provide for the applicable timeframe to perform the relevant obligation to be extended accordingly and for the parties to consult with each other as to how best to overcome and mitigate the force majeure event. However, some clauses may contain a long-stop date whereby if the relevant force majeure event persists for a certain amount of time, a right for one or both of the parties to terminate arises. Such clauses may come into play if the effects of the virus persist for a long period of time, such as with a long term closure.

Also read: Force Majeure Event in the UAE

Al Tamimi & Company’s Real estate lawyers regularly advises on hotel management agreements in the event of a force majeure event.

For further information, please contact Tara Marlow (t.marlow@tamimi.com) or Ian Arnott (i.arnott@tamimi.com).

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.