- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

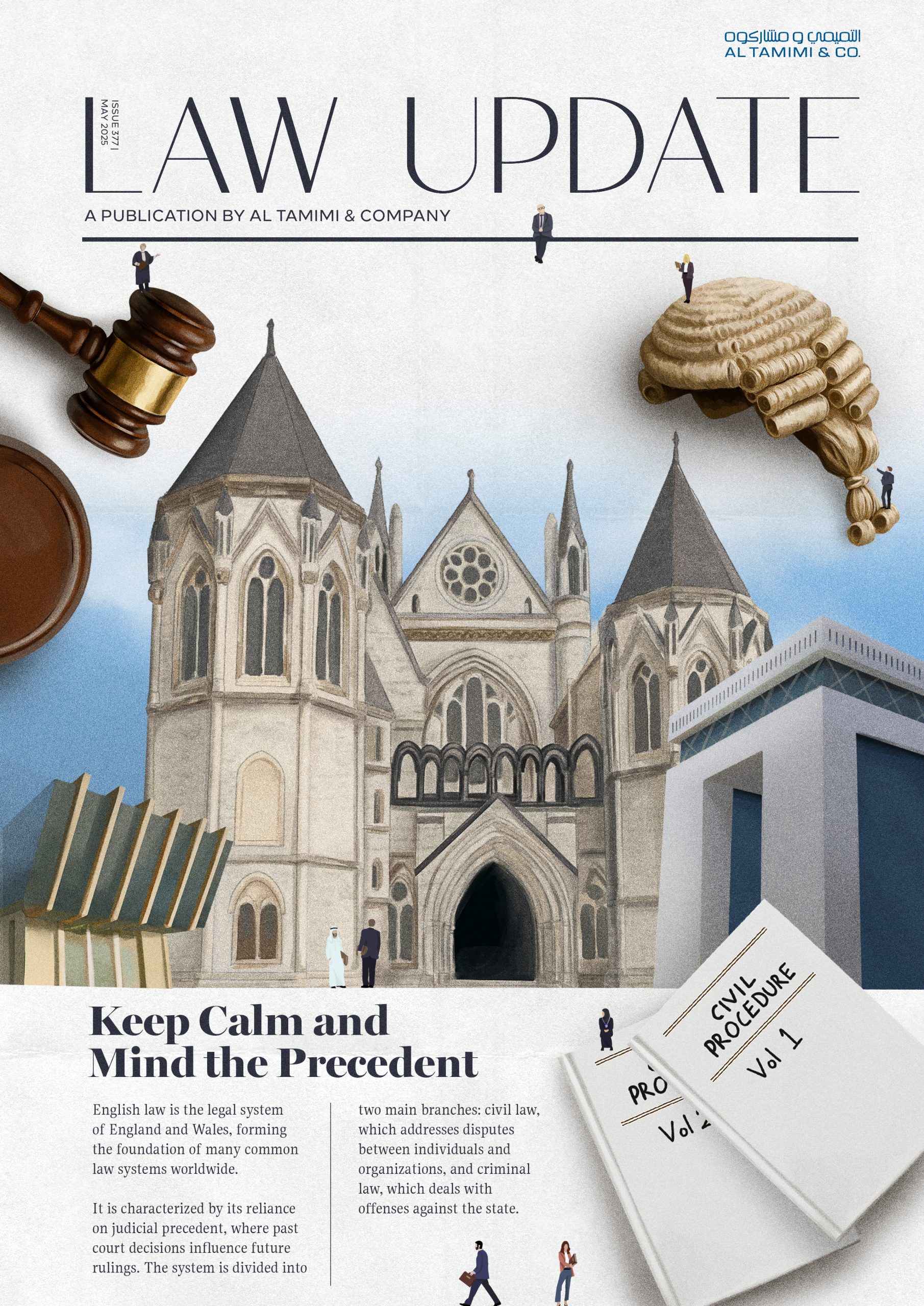

English Law: Keep calm and mind the precedent

In May Law Update’s edition, we examined the continued relevance of English law across MENA jurisdictions and why it remains a cornerstone of commercial transactions, dispute resolution, and cross-border deal structuring.

From the Dubai Court’s recognition of Without Prejudice communications to anti-sandbagging clauses, ESG, joint ventures, and the classification of warranties, our contributors explore how English legal concepts are being applied, interpreted, and adapted in a regional context.

With expert insight across sectors, including capital markets, corporate acquisitions, and estate planning, this issue underscores that familiarity with English law is no longer optional for businesses in MENA. It is essential.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- December 2014 – January 2015

- /

- Shifting Sands: Negotiating Risk For Ground Conditions

Shifting Sands: Negotiating Risk For Ground Conditions

Niall Clancy

December 2014 – January 2015

This is particularly so in the Middle East, where the civil codes of many countries in the region typically provide for the joint and several liability of the architect and contractor in respect of a total or partial collapse of a building or fixed works, for a period of ten years, even if the collapse is due to a defect in the land itself.

The risk

Many projects are designed and contracted without adequate site and subsoil or seabed investigations. While this may be suitable for some types of contract it is not suitable for all, as without being aware of all the potential risks no proper pricing of the work or final design is possible.

As an owner, if the contract is a construct only, you would want complete investigation to reduce the risk of time and cost blow outs.

Unforeseen or undetected physical conditions may necessitate change to the means and methods of construction and, in extreme cases, redesign of the structure. Often it is the case that contractors rely on the faulty geological information provided by the employer without undertaking a thorough investigation of their own – resulting in claims and delays. This is the situation that has emerged with the the high-speed railway linking Hong Kong with Guangzhou which is currently facing a delay of up to 2 years, partly due to unforeseen geology beneath an urban area of Hong Kong. The additional cost related to this delay is expected to run into tens of millions of dirhams.

This risk issue can be recast as “who bears the additional cost should the physical conditions at the site turn out to be something other than anticipated?”.

It is usual that the best outcome will most often be achieved where the party best placed to manage a risk takes responsibility for it. However this is often overlooked where the employer needs certainty of price and completion date, in which case the contractor may be paid a price to take on that risk.

Is local law relevant?

Local law always needs to be considered when negotiating and drafting ground condition provisions. Although each country in the Middle East has its own laws, the key considerations in most of them are that:

- parties have complete freedom to determine what contractual provision is made for unforeseen physical conditions;

- parties must act in accordance with their agreement (and in a manner which is consistent with the requirements of good faith) so careful thought must be given to drafting to ensure that all eventualities are covered;

- provisions which conflict with a mandatory provision of law are unenforceable, such as any risk transfer intended to limit the contractor or engineer’s decennial liability;

- carefully drafted disclaimers (such as in connection with an error or omission in a geotechnical report) will generally be enforced by the courts, provided that any misrepresentation (in the sense of incomplete or inaccurate information) is not gross or fraudulent;

- ignoring decennial liability, many laws, such as that in the UAE, do not explicitly provide for how the risk for ground conditions is to be allocated if the contract is silent. A court may decid to cancel all or part of a contract and return the parties to the position that they were in before the contract was made.

Any clause which relates to the risk and consequences of unforeseen ground conditions, including rights to extensions of time, change orders, force majeure, indemnities and insurance, needs to be considered in detail.

Risk in standard form contracts

The FIDIC Red Book (Conditions of Contract for Construction) allocates risk to the employer for physical conditions which were not reasonably foreseeable by an experienced contractor by the date for submission of the tender.

The main shortcoming of this clause, from the employer’s perspective, is that it diminishes the incentive on the contractor to fully investigate and account for the ill-effects of all possible ground conditions.

Whether or not a physical condition is foreseeable will depend on the specific circumstances in each case and is often highly contentious and thus costly. While not every dispute can be avoided through adequate negotiation and drafting, issues can be narrowed greatly through clear and concise drafting.

If there are reports and investigations that the contractor relies on, and others which are provided but are not relied on, then the contract should make this clear. All relevant reports and investigations should be referenced in the contract unless one party has accepted all risk.

The FIDIC Yellow Book (Plant and Design-Build Contract) contains more or less the same risk sharing provision as that in FIDIC Red Book. On the face of it the Yellow Book is equally unattractive to employers.

In stark contrast, the FIDIC Silver Book (Conditions of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects) makes it the contractor’s responsibility to obtain all necessary information in connection with physical conditions, and disclaims the employer’s liability for the accuracy, sufficiency and completeness of information he makes available to the contractor.

However, the Silver Book is based on the idea that the contractor will be given adequate opportunity to carry out its own site investigations.

In practice FIDIC contracts are frequently amended to change the allocation of risk between the parties.

When amending any standard form contract, care must be taken to ensure that any knock-on effects of changes to the physical conditions on other provisions (e.g. clauses dealing with variations and extensions of time) are fully considered and addressed to avoid ambiguities and discrepancies in the contract.

Final note

Disputes concerning unforeseen grounds conditions are hotly contested and expensive; therefore the allocation of risk in the contract needs to be carefully considered and balanced so that it is appropriate to the specifics of the project. It is also essential that the risk be clearly defined, including those documents relied on and those that are not. Such provisions backed by warranties, indemnities or releases should reduce the scope for later argument.

It is important that, prior to executing a contract, each party:

- consider the type of contract best suited to the project;

- consider the contractor’s entitlements to cost and time of changes necessitated by unforeseen physical conditions;

- to the extent possible, carry out its independent testing and sampling of the ground (both surface and sub-soil conditions);

- consider the effect of local law upon the enforceability of provisions allocating liability to the contractor for information provided by the employer; and

- check any amendments to the contract to ensure that the contractually agreed risk allocation is adequately reflected.

If you need any assistance our construction and infrastructure team can help you properly document your project’s contractual conditions.

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.